The Israeli Right and the Transformation of the State: A Study of the Centrality of Power and Religion in Decision-Making

“Where the Jewish plow concludes its last furrow, that is where the border will be set.” — Joseph Trumpeldor, a phrase adopted by Practical Zionism.

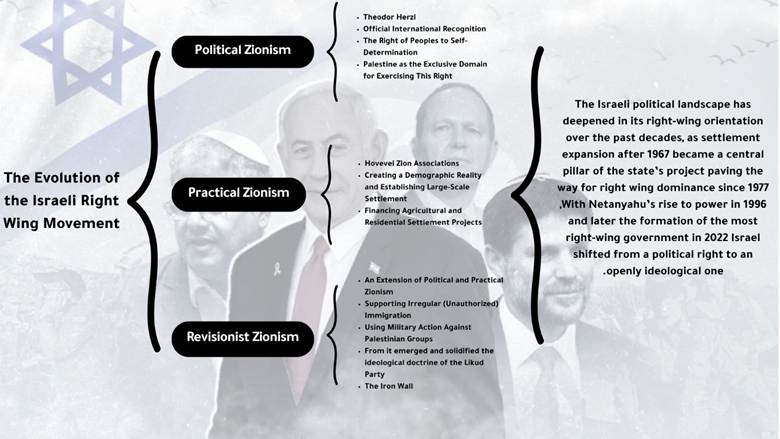

The roots of the Israeli right are essential to understanding the political and ideological configuration of the State of Israel and its contemporary trajectory. Although the Zionist project emerged with multiple wings and currents, the right-wing current formed early around a vision that combined militant nationalism and reliance on force to impose a new reality in Palestine. With the rise of Vladimir Jabotinsky’s ideas in the 1920s, the contours of what would later be known as the Zionist Right began to appear. Jabotinsky argued that the establishment of a Jewish state could not be achieved by diplomacy alone but required the construction of an “Iron Wall” — a force that would render the Jewish presence an irreversible fact on the ground.[1] This trajectory later became a pillar of political life in Israel and, after 1977, the dominant influence shaping state orientations, particularly concerning settlement, identity, and policies toward the Palestinians.

This tendency arose within a broader historical context that witnessed the ascent of early Zionist currents, foremost among them Political Zionism (ציונות פוליטית) under Theodor Herzl. Political Zionism proceeded from the assumption that the settlement project could not be realized through isolated initiatives or limited migrations but required formal international recognition to confer legal legitimacy on a Jewish polity in Palestine. Advocates of this approach grounded their discourse in the concepts of peoples’ right to self-determination and in designating Palestine as the exclusive geographic locus for the Jewish exercise of that right. This current was not merely a diplomatic appeal; it was an early attempt to construct a legal and political narrative that would grant the project international legitimacy, while largely disregarding the existence of a population already inhabiting the land and exercising its own right to self-determination.[2]

In contrast, Practical Zionism (ציונות מעשית) emerged within the movement as a current that dismissed the sufficiency of waiting for international recognition or legal endorsement; it maintained that the most effective path was to create a demographic and settlement reality on the ground through large-scale immigration and settlement in Palestine. The Hovevei Zion (Lovers of Zion) associations embraced this approach, promoting direct migration to Palestine and settlement in growing numbers on the premise that establishing a tangible Jewish presence would later secure legitimacy.

From faction to state backbone

Within this approach, agricultural and residential settlement projects were financed in Palestine alongside media and organizational campaigns to encourage Jewish immigration worldwide. Practically, Practical Zionism redefined the Zionist project from one that awaited international recognition to one that produced legitimacy through action on the ground, imposing a fait accompli to be negotiated after, rather than created by, negotiations.[3]

The right-wing current has transformed from a faction within the Zionist movement into a structural backbone of the Israeli state and a primary driver of its policies toward the Palestinians.

Revisionist Zionism (ציונות רוויזיוניסטית) represents both an intellectual and practical synthesis of Herzl’s Political Zionism and Practical Zionism: it inherited Political Zionism’s political-legal frame and Practical Zionism’s logic of on-the-ground action. Initially, Revisionist activists cooperated with the British Mandate authorities to facilitate immigration and settlement. However, disputes over policy and restrictions soon led them to break with the Mandate: they shifted from lawful, organized activity toward support for irregular mass immigration and toward the justification and use of violent military action against Palestinian groups to achieve their aims.

Ideologically, Revisionist Zionism articulated an uncompromising nationalist vision of Greater Israel that affirmed Jews’ right to impose sovereignty across the whole of Mandate Palestine and Transjordan. This practical and political conclusion had a direct impact on the Israeli party map: the Jabotinsky current provided the intellectual nucleus of the later Herut Party (חירות), from which the ideology and instruments of the Likud (הליכוד) consolidated — including the concept of the Iron Wall, which justified building an organized force capable of imposing facts on the ground and containing resistance rather than awaiting external legitimacy or relying exclusively on diplomacy.[4]

After 1967, these principles found their clearest institutional expression in the settlement project, which became the cornerstone of right-wing policy and of the right’s ascendancy since 1977, evolving into a dominant force in shaping state identity and policy toward the Palestinians.

Since Benjamin Netanyahu first assumed the premiership in 1996, the Israeli right has shifted from a political actor to the central axis of decision-making. This trajectory reached a high point in 2022 with the formation of a government widely described as the most right-wing in Israel’s history,[5] following the entry into the executive of hardline religious-nationalist forces and figures from the militant settlement stream — such as Itamar Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich. Their inclusion reinforced the transformation from a political right to a more explicit ideological right, unified in its approach to the Palestinians, the land, and the state’s identity.

The fusion of biblical narratives with military power has elevated violence from a political option to a religious imperative.

This evolution sought to concentrate instruments of governance and authority in the hands of a single current — the right — in an effort to reshape the state’s power structure in accordance with its ideological aims. Three years into this right-led governance, tendencies toward hegemony and the marginalization of other currents have intensified. Data from the Israel Democracy Institute indicate that the share of Jewish voters identifying with the right-wing bloc rose from roughly 46% in 2019 to about 62% prior to the 2022 elections,[6] reflecting a structural shift in public sentiment and the consolidation of right-wing influence in decision-making. Concurrently, the social base for extremist settler movements has expanded: beyond the “Hilltop Youth” and “Hilltop Girls”[7] and the “Price Tag” networks[8], more organized and militant groups have arisen — sometimes labeled the “Hilltop Monsters” — which adopt an increasingly radical discourse aimed at imposing facts on the ground through direct violence. Reports characterize some of these groups as highly violent, organized cells that assert a right to Greater Israel and reject any political or security settlement, even if proposed by the Israeli government. This marks a shift of such phenomena from the margins into the integrated political-security landscape, accompanied by growing official tolerance and a blurring of lines between these groups and state institutions.[9]

The descriptive framework of “religious security” in Israel: toward a new theory of doctrinal transformation of security doctrine

“Religious security” is an analytical framework that describes a transformation in Israeli security doctrine: away from a political-military approach grounded principally in deterrence and control, and toward an approach in which religion intersects with national security. Within this framework, religion functions as a reference for legitimizing decisions related to the use of force and the management of conflict on the ground, endowing confrontation with a theological dimension that makes the protection of identity and holy sites part of the state’s security function and imparting to the conflict a determinative — even providential — character that transcends conventional political calculations.

To clarify this conceptual framework, religious security can be decomposed into several characteristics that reveal its structure and practical implications:

- Centrality of sacred text in defining threat and security. The Torah and its interpretive traditions become tools for determining what constitutes a threat and what is a “religious duty” to defend, reframing security from a political logic to a sacred logic.

- Transformation of geography into a “sacred domain.” Land ceases to be merely a political or strategic resource and becomes a theological resource; territorial concession is thereby framed as doctrinal compromise.

- Integration of security and religious institutions. The overlap between religious leadership and the military-security apparatus deepens — through the ascendance of Religious Zionism within the armed forces and through the legitimization of security decisions by religious authorities.

- Militarization of the sacred and sanctification of defensive violence. The use of force is framed as a religious duty to protect the sacred.

The fusion of Torahic text with military power thus renders violence a religious duty rather than a mere political choice.

This transformation manifests across a range of indicators that show how the sacred permeates Israeli national security. At the theological level, Torahic texts and terminology have become commonplace in political and military discourse: one study found that David Ben-Gurion invoked Torahic or rabbinic references in roughly 79% of his wartime speeches, compared to 58% for Netanyahu,[10] and official documents increasingly employ concepts such as “divine right” and the “Promised Land.”[11] Religious references are invoked to justify military or settlement decisions, and rabbis participate in national and military rituals.

Political and legislative indicators point to the institutionalization of this tendency. These include the expansion of legislation with religious underpinnings related to land and identity — as documented by Adalah in a paper cataloguing several discriminatory draft laws[12] — the influence of religious parties within ruling coalitions and security committees, and the enactment of laws that legitimize religious settlements or public religious rituals. Court decisions that affect the status quo at sites of worship — for example, the transfer of certain administrative authority at the Cave of the Patriarchs to the religious council of the Kiryat Arba settlement — further reflect this institutional shift.[13]

These transformations deepen within the power institutions themselves: the proportion of religious personnel in the army and elite units has risen, rabbinic-military authority has expanded[14] settlers have received security privileges, religious guard units have been formed, the government has supported religious institutions operating in settlements, and military rabbis have participated in executive decision-making.

Netanyahu did not merely inherit the right-wing camp; he reconfigured it along scriptural lines that positioned religious doctrine as a central source of political decision-making.

The most visible outcomes on the ground are behavioral and operational: increased incursions into contested religious sites — most prominently the Al-Aqsa Mosque — the growth of ideologically motivated settler violence, the mobilization roles played by religious leaders in rallying settlers and soldiers, and the framing of military operations in religious narratives within Hebrew media. These indicators demonstrate the migration of security from a political-strategic domain to a theological-identity domain, where force becomes part of a historical-religious project rather than a mere instrument of the modern state.

Netanyahu and the contemporary Israeli right

Benjamin Netanyahu offers a gateway to understanding the deep transformation in the ideological architecture of the Israeli right. Long portrayed as the heir to the Jabotinsky school, he has in fact reworked the core of the right and introduced a more entrenched religious–Torah dimension. Political decisions and on-the-ground practices have acquired a doctrinal religious character, making analysis of Israel’s current policies contingent on understanding the complex interplay between Netanyahu’s political project and the ascendancy of Religious Zionism as a unified trajectory intent on imposing a new Torah-based reality in Jerusalem and the West Bank and on consolidating a power structure that redefines the state from within.

Netanyahu did not merely inherit the right; he reshaped it on Torah-based foundations, turning religious doctrine into a source of political decision-making.

This shift under Netanyahu has produced a new reality on the ground: right-wing power has moved from the instruments of governance to field action. The frequency of incursions has increased, particularly after 7 October, accompanied by Torahic rituals that are being legitimized in Jerusalem and at the Al-Aqsa Mosque. The right’s growing influence within government seeks to transform these practices from individual acts into officially supported faits accomplis, as part of a trajectory that aims to impose religious sovereignty over the site.

The integration of Religious Zionism into Israeli institutions therefore represents a structural change in the nature of authority and decision-making mechanisms. Religious discourse now functions as a direct guide for security and political decisions, a shift reflected in the escalation and geographic expansion of violations in the West Bank and Jerusalem. Doctrinal calculations now intersect with operational choices, rendering security institutions such as the police and the Ministry of National Security into executive instruments of a religious-national project that seeks to redefine sovereignty on a Torahic foundation.

With the rise of the right, Israel has increasingly legitimized certain religious practices and broken long-standing political taboos. The Feast of Tabernacles in the most recent year illustrated this trend: an unprecedented number of plant-based offerings were brought into the Al-Aqsa Mosque, and approximately 7,220 settlers were recorded entering the site[15] — an unprecedented figure for the occasion in recent years — a symbolic move intended to entrench Torahic rites within its courtyards and to normalize them as part of the “new reality.”

Speeches and positions of right-wing leaders that call for incursions into Jerusalem and the Al-Aqsa Mosque, and for praying there publicly, reveal the depth of the shift toward a religious doctrine used to justify violations and to impose religious sovereignty. While Netanyahu maintains that “the situation at the Al-Aqsa Mosque has not changed and will not change,”[16] National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir has taken the opposite stance. On Jerusalem Day he declared, “I am happy that Jews ascended to the Temple Mount — the Al-Aqsa Mosque — and reached there today,”[17] encouraging public Jewish prayer at the site in clear violation of the status quo that Netanyahu professes to preserve.

In this sense, the Al-Aqsa Mosque has become a testing ground for the imposition of Jewish religious sovereignty and an indicator of the profound transformation in Israeli decision-making.

These transformations are apparent in the escalation of violations across the Palestinian territories and their geographic spread to include wider areas of the West Bank and Jerusalem. Occupation authorities continue to issue increasing numbers of demolition and expulsion orders against Palestinian residents. Systematic demolition and clearance operations in and around the Al-Aqsa complex have raised concerns regarding the stability of its foundations and the risk of future collapse amid excavations and interventions that target both the structure and its symbolic significance.[18] Violence against Palestinians is no longer framed merely as a defensive response to protect settlers or to retaliate against attacks, but increasingly as a “religious duty” that expresses a theological conception of the state. Thus, Israel appears to be moving from a phase of “security occupation” to what may be described as a “doctrinal occupation,” which merges belief and policy and converts instruments of control into rituals bearing religious legitimacy.

This transformation indicates that the conflict in Jerusalem is no longer solely about political or security sovereignty but about the identity and religious-political meaning of the place. Every incursion into the Al-Aqsa Mosque and every attempt to establish a Torahic rite within its courtyards constitutes one step in a broader project to reshape the historical and geographic narrative of the city according to the doctrine of Religious Zionism. Understanding the ideological structure of the right — particularly its alliances with settlers and religious institutions — is therefore a necessary precondition for analyzing the emerging landscape, since the practices unfolding in Jerusalem today open the door to replicating this model in other Palestinian areas under a religiously legitimated framework increasingly integrated into the Israeli system.

Developments in Jerusalem are no longer confined to the Israeli-Palestinian arena; they now directly affect the core of Jordan’s national security.

This transformation carries particular significance for Jordan, given the Hashemite custodianship of Jerusalem’s holy sites. Attempts to alter the status quo raise political and security friction and elevate the Jerusalem issue to the center of regional balances rather than leaving it as a bilateral Palestinian–Israeli matter. Each advance of the Israeli religious-national project in the city, especially at the Al-Aqsa Mosque, is perceived in Amman as affecting Jordan’s legal and religious standing and as threatening the stability of arrangements that have held for decades. Accordingly, the Jordanian–Israeli relationship is governed by a sensitive calculus that combines security cooperation with political pressure: Jordan recognizes that any disruption of the balance in Jerusalem could have direct implications for its internal security, regional position, and relations with international actors engaged in the conflict.

Moreover, the growing influence of the religious current inside the Israeli government heightens Jordanian concerns about scenarios for the future of Palestinian administration in the West Bank and the prospect of unilateral arrangements that would bypass Amman’s historical role. Hardline right-wing policies also raise questions about the future of the Wadi Araba Agreement and its effectiveness as a framework for regulating bilateral relations — including critical arrangements on water, energy, and borders that form a cornerstone of regional stability.

From this perspective, Jordan does not regard Israeli transformations as isolated external developments but as a direct variable in its national security equation and a determinant of its position within the regional system. This prompts Jordanian policy to balance preserving security coordination channels with Israel while enhancing political and diplomatic levers through international institutions and Arab and Islamic frameworks concerned with Jerusalem. This delicate balance reflects an official recognition in Amman that the transformations in Israel are structural rather than transitory and that they require long-term strategic management to preserve Jordan’s role in Jerusalem and to prevent unilateral changes with broader regional repercussions.

Christian Zionism: the external extension of the Israeli religious project

The religious dimension of the Zionist project is not confined to developments inside Israel; it extends into a broader sphere in the form of Christian Zionism, a religious-political movement that emerged in the West — particularly in the United States — and advances a theological reading that regards the establishment of Israel as the fulfillment of biblical prophecies concerning the return of Christ. Advocates of Christian Zionism hold that the return of Jews to Palestine is a religious prerequisite for the Second Coming, and that establishing Jews in the “Promised Land” constitutes a divine command and a religious duty that fulfills messianic Torahic prophecies. In this way, the notion of “return” became first a theological project and later assumed a political dimension within Jewish Zionist thought.[19]

This religious dimension has deeper roots in earlier Christian theological interpretations, notably in St. Augustine, who articulated a scheme based on three tenets:

- that the Jewish nation had lost its covenantal role after the coming of Christ;

- that the Jews’ expulsion from Palestine was divine punishment for the crucifixion; and

- that the prophecies concerning their return had been fulfilled historically with the return from the Babylonian exile under Cyrus and thus required no future fulfillment.

This outlook shifted radically in the nineteenth century with John Nelson Darby, who proposed a doctrine of two kingdoms — an earthly kingdom represented by Israel and a heavenly kingdom represented by the Church — thereby reviving the notion that God’s promises to the Jews endure. Under Darby’s framework, supporting the establishment and consolidation of a Jewish state in the Promised Land becomes a religious duty for Christians intended to prepare the stage for the Second Coming.[20]

This movement provides the external doctrinal framework that lends theological and political support to Jewish Zionism. Both doctrines converge on a central idea: the “restoration of the Holy Land” and the “building of the Temple” are steps deemed necessary for divine salvation.

Through this convergence, Christian Zionism has become a strategic ally of the Israeli project, contributing to the reframing of the conflict over Jerusalem as a sacred religious struggle rather than merely a political dispute over rights and sovereignty. The concept of Armageddon (הר מגידו, “Har Megiddo,” the hill of Megiddo) functions as a doctrinal motif motivating a sizable segment of evangelical circles in the West — particularly in the United States — who regard a final cosmic battle, geographically tied to historic Palestine, as a precondition for the Second Coming. This linkage renders Jewish presence and Israeli control over Jerusalem part of an assumed theological trajectory toward salvation.[21]

This support has manifested in U.S. rhetoric and policy over recent decades — for example, in recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and in justifications of settlement expansion within narratives of “fulfilling the divine promise.” Such developments have strengthened the position of the right within Israel and conferred international political cover for its efforts to assert religious sovereignty over the city.

Theological backing from Christian Zionism therefore helps explain part of the transformations within the Israeli right. External support has not remained merely a Western religious posture but has become an influential factor within Israel’s domestic political environment. With the rise of the nationalist-religious right and the decline of secular currents, the religious narrative surrounding the “Promised Land” and the “Temple” has been incorporated into domestic political discourse and used to justify settlement expansion and modification of the Jerusalem status quo.

Conclusion

Tracing the development of the Israeli right indicates that the transformations experienced by the state are neither circumstantial nor confined to electoral cycles; rather, they reflect a long-term structural trajectory that has reshaped the Israeli political system. From the revisionist roots established by Jabotinsky to the rise of the religious-nationalist alliance in recent decades, the integration of religious doctrine with instruments of state power has accelerated to the point where security and religious ideology are not merely components of the system but primary determinants of state policy toward the Palestinians and of Israel’s regional strategy more broadly.

Political data suggest that the right has ceased to be only a dominant electoral bloc and has become a governing structure intent on consolidating a permanent system for managing the conflict through settlement expansion and redefinition of the West Bank’s and Jerusalem’s legal status. This transformation coincides with external theological-political support — notably from Christian Zionist currents — which helps legitimize these policies and offers them international political cover. These trends suggest that the next phase will likely involve continued entrenchment of a reality characterized by gradual annexation, the expansion of religious actors’ authority within state institutions, and the positioning of Jerusalem and the Al-Aqsa Mosque as central axes in the formation of identity and sovereignty.

At the societal level, profound shifts in Israeli collective consciousness have underpinned this rightward trajectory. Civil and secular values that marked early Zionist stages have declined in favor of a religious-nationalist value system linking “Torahic salvation” with “geographical sovereignty.” Consequently, Israeli national consciousness has become saturated with a messianic vision that regards control of the land as an extension of belief, producing a widening gap between liberal elites and a populace more inclined toward conservative religious identity. Thus, the rise of the right is not solely the result of electoral calculations but also reflects a cultural-value transformation that has redefined citizenship and belonging within the state.

Regionally and internationally, the rise of the Israeli right has reshaped balances of power and alliance patterns. The horizon for traditional political settlement has narrowed in favor of new security arrangements that align Israel pragmatically with certain Arab regimes as a counter-balance to Iran and to non-state actors. Concurrently, waves of populism and conservatism in the West have provided an ideological base for Israeli policies, precipitating the convergence of two rights — religious and nationalist — that share a discourse integrating identity, security, and religion.

Overall, Israel appears to be consolidating a “religious-security state” model in which military power and theological sanction are regarded as the bases of legitimacy and survival. In the absence of effective international pressure and with the weakening of the domestic liberal current, this trend is likely to deepen the divide with the Palestinians and to redraw the boundaries of the conflict on doctrinal grounds rather than on purely political ones. Hence, the Israeli right is not a transient political phase but an emergent ideological formation that redefines state, society, and identity in Israel, and that opens the door to a more confrontational phase in relations with the Palestinians and the broader region.

[1] The Iron Wall (Original in Russian, Razsviet, 4 November 1923). https://en.jabotinsky.org/media/9747/the-iron-wall.pdf?utm_

[2] Farouq Muhammad Judy, Zionism and the Hebrew Language, Cairo: Red Sea Library, 2024, p. 18.

[3] Ibid., p. 21.

[4] Ibid., p.33

[5] BBC Arabic, “Israel: Agreement on What Is Considered the ‘Most Right-Wing’ Government Led by Benjamin Netanyahu,” December 22/January 2022, https://www.bbc.com/arabic/middleeast-63993806.

[6] Times of Israel, “Jewish Israeli voters have moved significantly rightward in recent years, data shows,” 29 August 2022,https://www.timesofisrael.com/israeli-jewish-voters-moved-significantly-rightward-in-recent-years-data-shows/?utm_

[7] Hilltop Youth: These are groups of extremist settlers who adopt a violent approach aimed at displacing Palestinians and entrenching settlement control. They seize hilltops overlooking Palestinian villages and farmlands, gradually expanding them into outposts. They have carried out numerous acts of killing, arson, and attacks on homes and property.

[8] Price Tag Group: This is an extremist youth group that has carried out attacks on the property of Palestinians and Arabs inside the Green Line, intentionally leaving racist slogans and signatures at the sites of their operations.

[9] Al Jazeera Network, “The ‘Hill Monsters’… A Terrorist Group that Terrifies Palestinians and Alarms Israel,” November 10, 2025, https://www.aljazeera.net/politics/2025/11/10/وحوش-التلال-جماعة-إرهابية-ترعب.

[10] Ynetnews، “Ben-Gurion used more religious references in speeches than Netanyahu, study finds”، 7 march 2025, https://www.ynetnews.com/jewish-world/article/rjtqvwzrll?utm_

[11] Full text of Netanyahu’s speech: We won’t let the world … The Times of Israel, 26 September 2025, https://www.timesofisrael.com/full-text-of-netanyahus-speech-we-wont-let-the-world-shove-a-terror-state-down-our-throat/

[12] Adalah, New Discriminatory Laws and Bills in Israel, 14 September 2010. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2009_2014/documents/dplc/dv/adallah_discriminatory_isra/adallah_discriminatory_israel.pdf

[13] Israel Hayom, “Israel assumes control over Cave of the Patriarchs”,16 July 2025 https://www.israelhayom.com/2025/07/16/israel-assumes-control-over-cave-of-the-patriarchs/.

[14] The Guardian, “National religious recruits challenge values of IDF once dominated by secular elite 18 July 2024 https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/jul/18/national-religious-recruits-challenge-values-of-idf-secular-elite

[15] A field-based source

[16] Reuters, “Netanyahu says no change at Al-Aqsa after Ben-Gvir’s remarks”, 24 July 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/netanyahu-says-no-change-jerusalem-holy-site-contradicting-minister-2024-07-24/?utm_

[17] Sam Sokol, “Breaching status quo, Ben Gvir says it’s his policy to let Jews pray on Temple Mount,” The Times of Israel, 5 June 2024, ، https://www.timesofisrael.com/liveblog_entry/breaching-longstanding-status-quo-ben-gvir-says-he-allows-jewish-prayer-at-temple-mount/?utm_

[18] [18] wafaa، “Jerusalem Governorate warns of collapse of parts of Al-Aqsa Mosque due to Israeli tunnel digging”,22 October 2025، https://english.wafa.ps/Pages/Details/163612?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[19] Encyclopædia Britannica, “Christian Zionism”, Encyclopædia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/topic/Christian-Zionism.

[20] Al Jazeera, Without Borders | Mohammad al-Sammak with Ahmad Mansour: Christian Zionism, YouTube video, December 25, 2002, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8WfF_ziyuz4.

[21] Clark, Victoria. Allies for Armageddon: The Rise of Christian Zionism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.